Investment Intelligence When it REALLY Matters.

Investment Intelligence When it REALLY Matters.

America's Eroding Job Quality

Taken from September 2012 Vol 40, Intelligent Investor

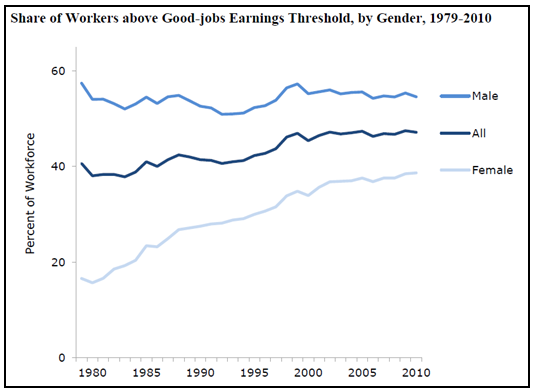

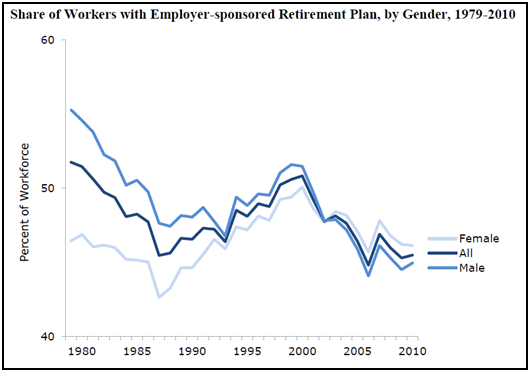

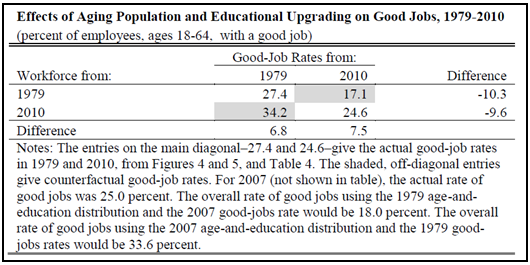

The U.S workforce is significantly older and better educated than in it was during the 1970s. Because older, more-educated workers tend to earn more and receive better benefits than younger, less-educated workers, we would expect to see workers with a higher share of “good jobs.” But this has not been the case.

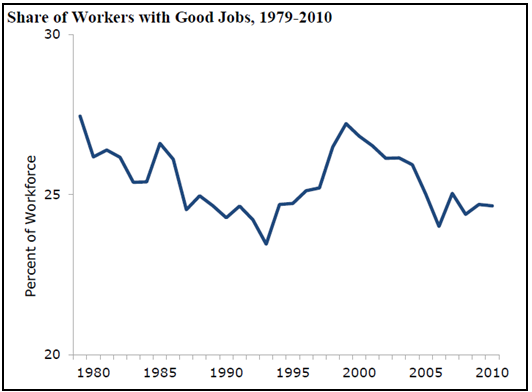

In this discussion, the bar for what constitutes a “good job” has been set quite low. A “good job” has been defined as one that pays at least $37,000 annually and has both employer-sponsored healthcare and retirement benefits.

According to the data, the share of the labor force that had a good job declined from 27.4% in 1979 to 24.6% in 2010. But how much of this decline has been due to the economic crisis?

Prior to 2007, the share of the labor force that had a good job was still only 25.0%. In conclusion, since 1979, the U.S. economy has lost between 28% and 38% of its capacity to generate good jobs.

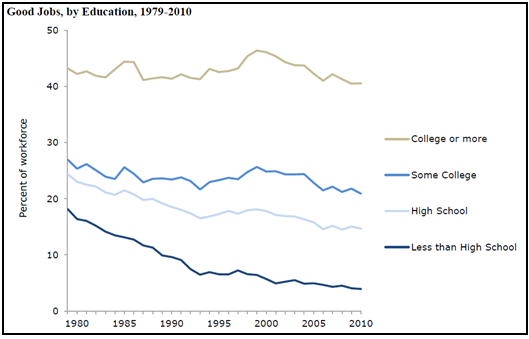

The most common response from critics of this trend is that workers’ skills and education have not kept pace with technological changes demanded by the workplace; the so-called structural unemployment argument. However, if this were true, we would see a higher share of workers holding advanced degrees with good jobs today.

Instead, at every age level, workers with a four-year college degree or more are less likely to have a good job than three decades ago.

The real cause of these worrisome trends is due to the following:

1) The effects of globalization, or more specifically, America’s so-called “free trade” policy.

2) Suppressed minimum wage.

3) Decreased ability of workers to engage in collective bargaining arrangements due to the decline in unionization rates.

4) Open and “fast-track” immigration in part due to multiculturalism.

As a result of these shifts, low– and middle-income workers have been placed in direct competition with workers in developing nations which due to differences in trade and economic policy, are willing to work for lower wages.

In recent publications we have discussed the first and second causes of inequality (above). Here, we examine the effect of unions on inequality.

The decreased ability of U.S. workers to freely join and form unions and participate in collective bargaining has been another piece to the income inequality picture.

For years, Americans have been told that labor unions are bad. The most common portrayal of unions is that its members are greedy and demand wages that are excessive. As evidence of this, union critics invariably point to the United Auto Workers Union (UAW). Of course, the UAW is the poster child for the less desirable aspects of unions.

During a period when unfair trade and low minimum wage laws have sent millions into poverty, labor unions in the America have never been more important. Yet, they continue to lose influence as membership declines.

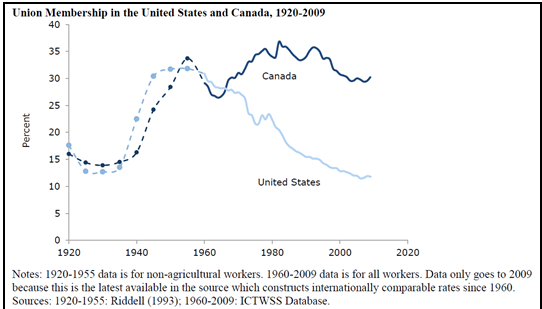

Upon passage of the National Relations Labor Act of 1935, the unionization rate in the U.S. rose appreciably. But since the early-1960s, the rate unionization has been in decline.

Many economists and policy makers have provided a variety of reasons accounting for this trend. Some of the more common arguments are related to structural changes to the economy or the work force, such as technological change or globalization.

According these arguments, as the economy shifted from manufacturing to service, the blue-collar male worker has been replaced with education white-collar male and female workers, who are less inclined to favor union membership. However, there are elements found in the “modern economy” that would cause workers to oppose union membership when compared to the “old economy.”

In addition, the argument that women are less likely to join a union simply does not stack up. According to some estimates, females are expected to make up the majority of union members in the U.S. by or before 2020.

Finally, if declining unionization rates have been due to structural changes in the economy, we would expect to see a similar trend of declining unionization in Canada. Let’s take a closer look at the data on unions in the U.S. and Canada.

But before we begin, is there any relationship between union membership and high-income earners?

As the first chart shows, there is a fairly high inverse correlation between the level of union membership and the share of income going to the top 10%.

One of the least mentioned factors accounting for declining union membership have been employer opposition to unions. Here we compare the differences between unions in the U.S. and Canada.

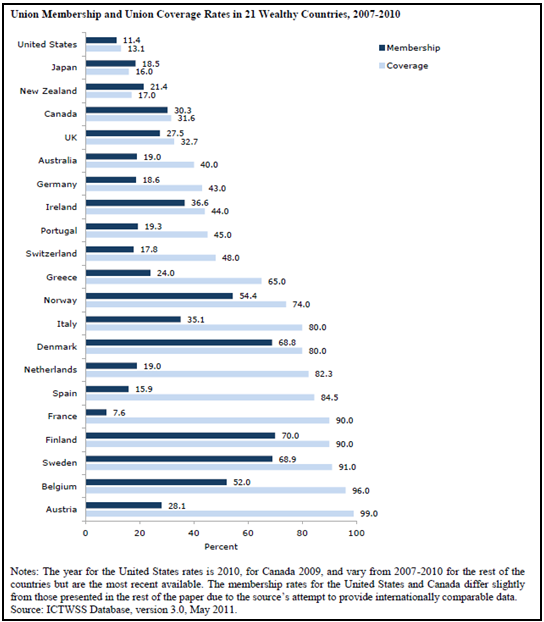

During the early 1950s, unionization rates in the U.S. and Canada were the same at roughly 33%. Then in the 1960s, they began to diverge.

As of 2011, the unionization rate in the U.S. stood at just 11.8%, while it was 29.7% in Canada.

The strength of unions in Canada is largely the result of two labor policies which are absent or deficient in the U.S. First, several regions of Canada have a very simple process for forming unions known as “card-check authorization.” All this means is that a majority of employees sign union authorization cards and then submit them to the labor board for verification in order to certify the union.

In contrast, the process is very long and tedious in the U.S. In short, the ball is in the employer’s court and it is up to the employees to fight to push the union through.

During the process, employers often initiate anti-union campaigns consisting of coercion, intimidation, employee termination and other behaviors in order to discourage union participation. Of course, many of these activities are illegal, but current labor policy has not even attempted to deal with these issues.

Up until the late-1970s, all provinces in Canada certified unions through card-check authorization. But in recent years, provinces have shifted to mandatory elections which is the process used in the U.S. As a result of this change, Canada has experienced a decline in unionization.

The second difference is that Canada has what is known as “first contract arbitration,” which allows for collective bargaining to move past numerous stalling tactics by employers.

There are many other differences in the union structure accounting for the large difference in unionization rates between the U.S. and Canada.

For instance, in some parts of Canada, temporary or permanent striker replacement is banned. In contrast, no such ban exists in the U.S.

In addition, close to one-half of states in the U.S. contain “right-to-work” clauses in employment contracts, whereby all employees covered by a union (even though not necessarily union members) are required to pay representation fees to the union. In Canada, “right-to-work” clauses are not included in contracts.

The overall difference between the unionization process seen in the U.S. versus Canada appears to be that the legal process for unionization and first contract arbitration in the U.S. erect enormous barriers which discourage and even prevent employees from forming and joining unions.

As a result, the collective bargaining process in the U.S., which once served to offset corporate exploitation, is all but dead.

See Also

Free Trade And The Suicide Of A Superpower (Part 1)

Free Trade And The Suicide Of A Superpower (Part 2)

Free Trade And The Jewish Mafia

Ford As A Crystal Ball For America

Washington's War Against America's Middle Class

Video: Educating A Libertarian Hack From Harvard

7 Myths About US-China Trade and Investment

The Dirty Secret about Hedonics & Globalization

Thailand, Globalization and Real Estate Economics

America. What Went Wrong? (Part 1)

America. What Went Wrong? (Part 2)

America's Second Great Depression

The Death of Labor Unions in America

Record Profits and the Huge Sucking Sound of American Jobs

The Death of Labor Unions in America

Unfair Trade Promises More Job Losses